“We wander the planet looking for members of our tribe. Once in a while, if we’re lucky, we find them.”- John Byrne Cooke

In the winter of 1996-’97, at the close of an intense three-year period of nearly constant, ferocious performances to a cult-like regional following accompanied by a profusion of songwriting, our band The New Tribe was mysteriously dissolving. We didn’t quite know why this was happening, but there were plenty of reasons. We were all barely out of our teens, pulling in different directions musically and personally. We were burned out from touring and earning very little from shows, working in restaurants to pay the rent. On a fundamental level, perhaps the intensity of those few years had simply taken a toll, and the whole endeavor had to be put aside so that all of us who were involved could pursue other paths, other musical expressions, and other ways of being in the world. One night at a club in our homebase of Norman, Oklahoma, during the set break we turned to each other without fanfare and said, ‘it’s done.’ It was hard to get our heads around not just the ending, but the whole trajectory of the experience of being in that band, and in the community it created.

In today’s world, the name ‘The New Tribe’ no doubt could strike some as trite (at best). But the name and the idea of a broader community with a band at its heart, grew organically as a response to our upbringing in American suburbia in the 1980s. We spent most of our childhood in Houston, moving ever further out from the city center, from one suburban home to another, as the city sprawled on. The suburbs were alienating, places full of good people lost in the dream. Strip malls, Reaganonomics, and consumerist culture were the backdrop of what Garcia called “the new lame America”. We hung out in vacant houses, drank Budweiser, cheap Canadian whiskey, Strawberry Hill. We were skaters, we liberated wood from the construction sites that were everywhere in Houston during the oil boom days and built half-pipes and launch ramps. We loved punk rock and new wave, forms of expression that spoke out against the social structures we were learning to loathe, and hinted at other worlds. But we were also open to the many other genres of music in the ambient environment around us — country, R&B, rap and hip-hop, classic rock, and 50’s and 60’s stuff are parents liked. Music had always been a thing for us; when we were barely old enough to press record on a tape deck, we called ourselves The Funky Funky Chipmunks and recorded ourselves singing ‘The Gambler,’ ‘Back in Black,’ and ‘Runnin’ with the Devil.’ We learned instruments eventually — guitar, bass, drums, and keyboards — and started proper garage bands. We got super drunk and played incoherently to our drunk friends. We got high and starting writing real songs.

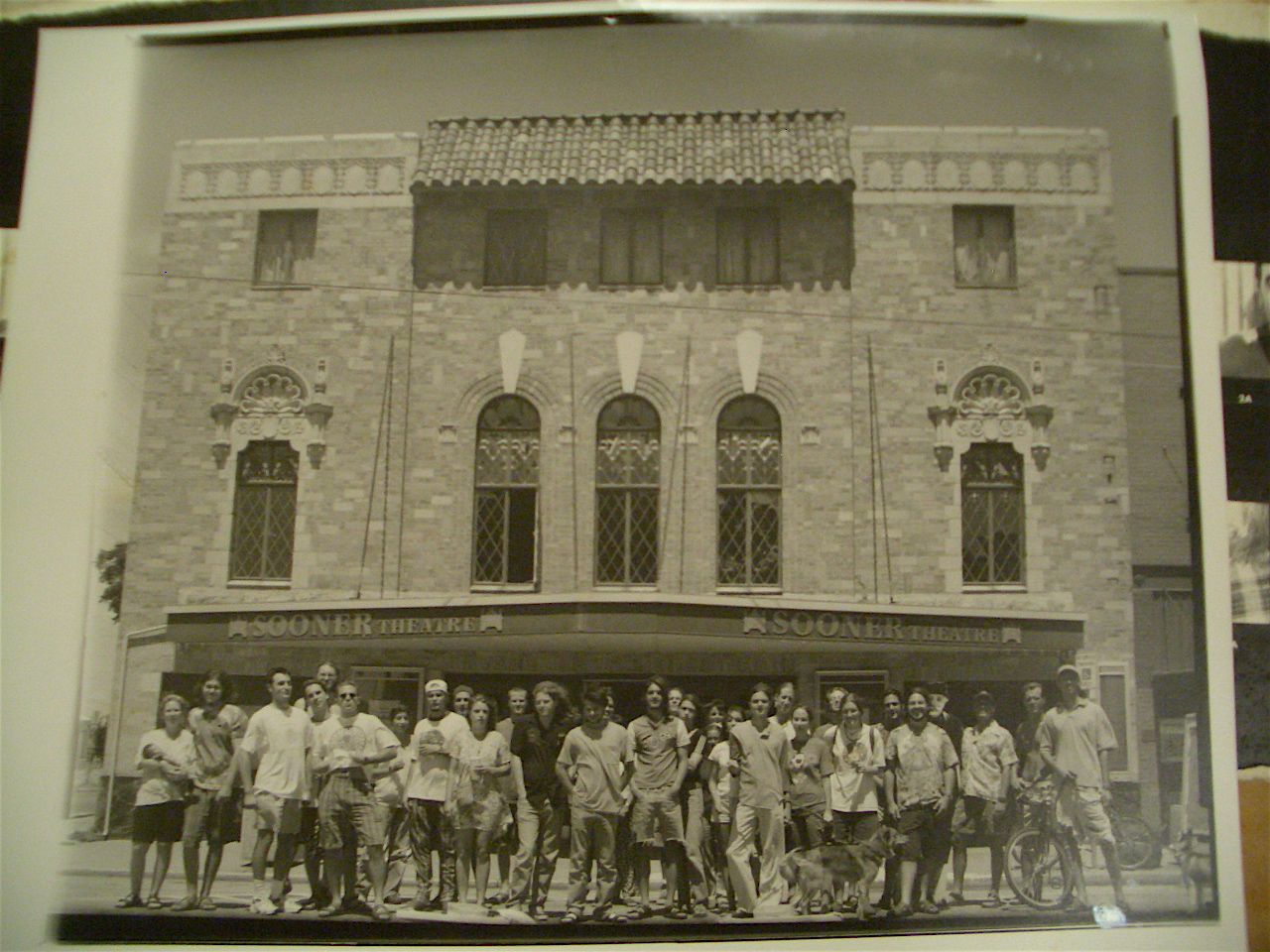

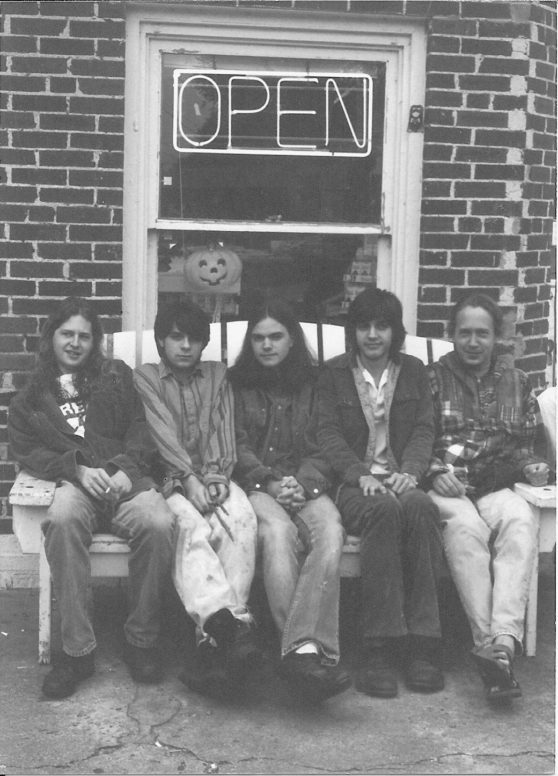

And then we moved to Norman, Oklahoma. That little college town was an oasis to us after the anomie and violence of the Houston suburbs. There was a groundedness in Norman, a sense of history, community, and intellectualism that we didn’t fully know we were missing until we got a taste of it. In the early ‘90s, Norman was a funky place with a very vibrant music scene. The Flaming Lips were blowing everyone’s minds in local venues, of course, but there were tons of other great bands, most of whom you’ve probably never heard of: Love Button, Mandala, Street People, Limbo Cafe, The Silver-Tongued Devils, Legghead, Local Hero, Blemish, The Nixons, Barnyard Slut, and many others. We went to any shows we could get into as underage kids, and cast about for musicians to form a band with. Then we met Chris Gomez, who quickly became a part of the band and a brother to us. It was not long after Gomez joined that we decided to call ourselves The New Tribe, which for us meant a new community of open mindedness and inclusion, free expression and an embrace of more collectively oriented values. Our idea from the beginning was that the band would be a catalyst in this community. And that’s what happened. The three of us — Eric, Adam, and Gomez — would be the core of the group for the next three years while a number of other great players and comrades came and went, including Mike Hosty, Dean Avants, and Mike Phenix. In addition, two great percussionists, Lawrence (Booty) Linden and the spaceman John Metcalf, joined the band at various times.

“What I like best about music is when time goes away.” – Bob Weir

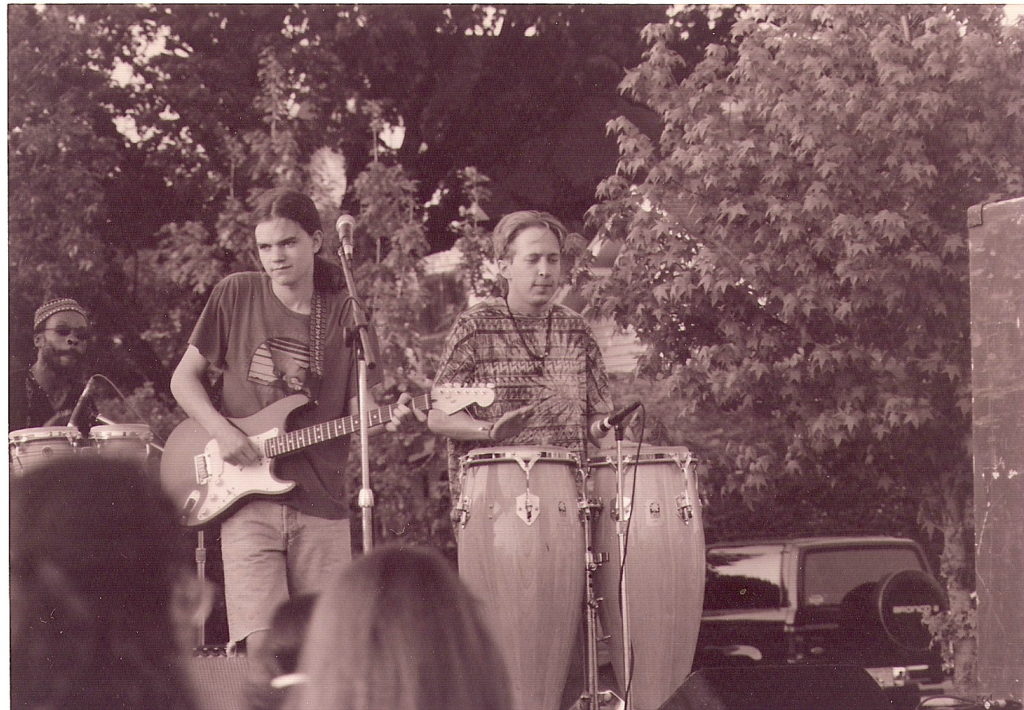

With half the band still in high school, we started playing the local club circuit, beginning with a memorable stretch in the summer of 1993 on Monday nights at the Liberty Drug, with a one-dollar cover. Each week the show got bigger, and before long the band enjoyed a regular devoted fan base that attended nearly every show. With an emphasis on improvisation, never repeating the same set twice and constant addition of new material, the shows were an event to behold and be a part of. Looking out at the crowd, we saw a writhing mass of dancing bodies, and that mass of movement and energy both followed us in our onstage explorations and drove us forward with an outpouring of energy and spirit. The material covered quite a bit of ground stylistically but always had enough of a groove to get the audience moving and enough spacey-ness to transport you to other places. The sound was a unique blend of the primal, soulful, rhythmic side with roots from AM radio, disco records, and even Texas Hardcore, and the cerebral, musical side inspired by psychedelia, jazz and world music. Over the course of the band’s run songwriting remained important and everyone contributed. We emphasized having three to four songwriters and singers, something that set us apart from other bands. An overarching pop sensibility kept things accessible and helped avoid the self-indulgent tendencies that some improvisatory bands can fall into.

A word on improvisation in The New Tribe: the improvisation, the impulse to experiment, really started for us before the band came into being, when we had the opportunity to play with a family friend from Taos, guitarist Tracy Manning of The Shemps. Tracy’s knowledge and love of stuff like the Grateful Dead and Allman Brothers was passed on to us through hours of open-ended jamming with Tracy as our guide. We also had the chance to learn from and observe some local cats that played in a smokin little jazz quartet in the 50’s tradition of Miles, Coltrane, Thelonius Monk, etc. A whole new dimension and way of looking at music opened up and once the band began filling clubs with dancing patrons, the need to extend pieces and grooves indefinitely took it even further. Long shows of three hours were the norm. We couldn’t help but get better at performing as we logged so many hours on stage. We idolized the Beatles in their raw and rowdy Hamburg days, where they forged their sound and their mutual bond by playing for hours on end in seedy bars.

“It’s been pointed out by Scott Joplin and others that the origin of jazz solos and improvisations was a pragmatic way of solving a problem that had emerged: the “written” melody would run out while the musicians were playing, and in order to keep a popular section continuing longer for the dancers who wanted to keep moving, the players would jam over those chord changes while maintaining the same groove.” – David Byrne

Time passed very quickly in those few years. We were constantly busy, and the scene around us was flourishing. In addition to constant shows, both ours and those of other bands, there were parties, festivals, potluck dinners, band meetings, communal houses, jobs to work, businesses to start, road trips, couples forming and parting ways, babies being born, and all of the other things that create a community. But from a professional musician’s standpoint, despite all of this and the local and regional success the band enjoyed and some notable gigs around the country, there was a frustrating lack of ability to escape the orbit we found ourselves in. And as noted above we were very young, and soon found ourselves wanting to branch out and try different paths away from each other. So it eventually came to seem like a natural progression to let the group die, and for us to move on. Adam went west, out to Oregon, and Gomez, Eric, and Mike Phenix headed east, to New York. We all went on to form other bands and solo projects, sometimes in various combinations with one another. Time and life went on.

Over time though, Norman always drew us back into its center of gravity, as it does for many folks. In the fall of 2016, the Tribe played our first show in nearly two decades, at the Chouse in Norman, in honor of our mom’s 70th birthday. We thought of it as a one-off for the party but something unexpected happened when the first rehearsal went down. Without any discussion, review or preplanning, we played through the first tune (Stephen’s Song) nearly perfectly in one take. And the music had a power that possessed our bodies and animated us in ways that can’t be described here, ways that we had virtually forgotten. It felt like all of the energy and power of those few intense years back in the ‘90s had simply lain dormant all that time, waiting for the chance to express itself again. That resurgent power then guided us through the show at the Chouse and then other shows around Oklahoma and Texas, and then into the studio to make the record that we were never able to make back in the day.

“Without music, life would be a mistake.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

We convened in January of 2017 and set up a recording studio at Oklahoma City’s iconic venue, The Blue Door, which our old friend Greg Johnson generously opened up to us for ten days of intensive music-making. Phil Harris, sound engineer and longtime member of the broader Tribe community, brought his mobile recording rig out from Nashville, and we worked eight or ten hours a day for a week and a half laying down tracks. The goal was to capture the dynamism and energy of a live show, the context in which we have always thrived. So the majority of the tracks were done together live, and we added vocals and some of the instrumental solos on top later. We mixed the record ourselves, with a lot of help from Mike Phenix and a little help from Wes Sharon, both of whom have amazing studios in Norman. Mike Phenix then mastered the album. The final product contains ten songs, nine of which go back to the early days of the band, and one of which is new. We feel that the album captures the magic of the intense early period of New Tribe activity in ways that we may not have been able to achieve back then when we didn’t have the knowledge of the studio or the consistency in our playing that we have now. At the same time, we wanted to include a new song to point the band forward. The New Tribe has always been about change and exploration, pushing at boundaries and experimenting. We’re delighted to share this record, the fruit of more than twenty years of making music and living. And we are equally excited to be writing and recording more new material moving forward, playing more shows, traveling new paths.

Thanks for listening and being part of this.

Much love and happiness,

Eric and Adam Sarmiento (on behalf of the broader New Tribe)